It seems certain that AI in 2025 will be full of surprises. Just one month into the new year, we’ve already seen the emergence of DeepSeek and the accelerating race for AI sovereignty marked by the Stargate project. Among such uncertainties perhaps there’s only one thing you can bet on – that even these developments may seem distant memories by June.

Nations, big tech companies, and VC-funded startups race towards AGI – when I hear these big words discussed in the media, I sometimes think to myself: What voice do the billions of people whose lives will be transformed have in this process? AI is increasingly woven into the fabric of our daily lives, and this integration will only deepen. This technological transformation isn’t just a change in tools – it fundamentally reshapes how we live. Must the majority of us merely accept the technological future shaped by a select few? Can we trust these decision-makers to act in humanity’s best interest?

The proposed visions of AI certainly stretch our imagination: liberation from tedious work, enhanced creativity, increased productivity, space exploration, and even transhumanist evolution. Yet every advance brings trade-offs, and most people are too caught up in daily life to consider whether this future — if it’s in fact achievable — aligns with their values and the lives they wish to live.

AI ethicists in this light could be seen as those who grapple with this future on our behalf – a future that is simultaneously present and yet to arrive. But they too feel powerless against those grand narratives and sweeping changes. Those who speak up about ethical concerns increasingly find themselves disheartened. The volatility of the field is stark – witnessed in how Trump’s administration swiftly dismantled Biden’s AI executive order. And AI ethics professionals struggle with burnout as they navigate ever-shifting guidelines. While major players like OpenAI speak of ethics, their words ring hollow, making it difficult to maintain hope for meaningful ethical oversight.

Where do we stand with AI ethics now?

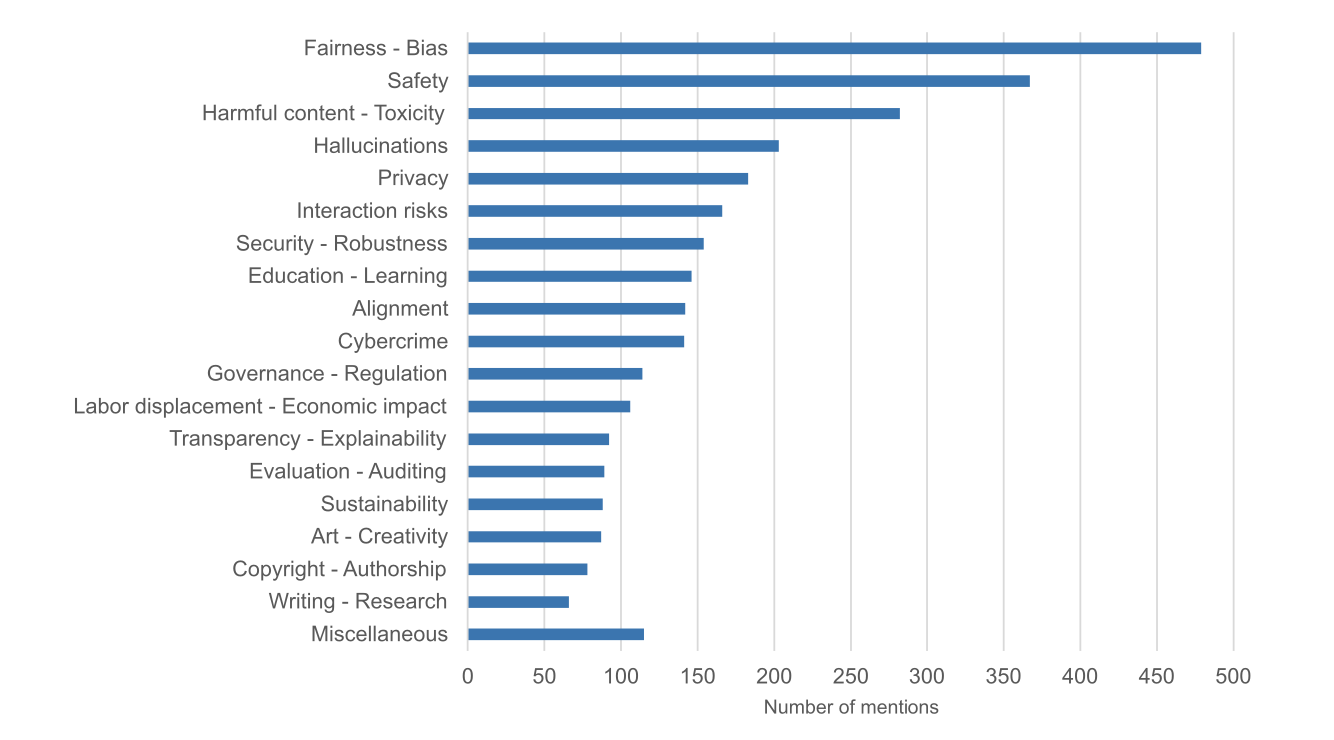

While the field encompasses diverse voices and activists, the dominant AI ethics discourse has largely centered on issues of fairness, bias, and safety. The focus has primarily been on top-down solutions – creating regulations to compel companies to address these issues and raising public awareness. This approach is well-documented in Thilo Hagendorff’s 2024 paper..

Initially, AI ethics focused on creating lists of ethical principles, but since then has shifted toward implementing these principles. All in all, it’s fair to say that the focus has largely been confined to issues that can be addressed through technical solutions — making AI systems explainable, fair, private, and safe — primarily because these are problems that developers can tackle directly.

This technical focus, while practical, has led AI ethics to drift from one of its important roles: identifying broader societal harms and considering impacts on those outside the tech community. While prioritizing solvable technical problems is understandable, this approach reflects a kind of technological solutionism.

However, if AI fulfills its promise to replace or augment human expertise across domains, its adaptability means it will inevitably become entangled in the ethical and political dimensions of the practices it touches too. Many critical areas in AI ethics cannot be addressed through technical fixes or checkbox compliance alone – issues like social cohesion, democratic values, public-private partnerships, and environmental impact. Yet these crucial concerns seem to receive insufficient attention in current AI ethics discussions.

As the field grows increasingly technical, it creates an implicit barrier, suggesting that only experts can meaningfully participate in AI governance. The public is relegated to the sidelines, offered educational materials and events about AI at best, while remaining excluded from real decision-making.

The Three Layers

A friend of mine with a PhD in ethics recently remarked, “I’m sometimes confused by the way people talk about ‘AI ethics’ nowadays — it got me thinking, ‘where is the ethics in all this?'” Indeed, today’s AI ethics discourse seems to bear little resemblance to traditional ethics studies, which pursues questions about what constitutes a well-lived life and how humans can flourish. Again, this disconnect exists largely because current AI ethics discourse mainly revolves around technical fixes and regulation. The gap sometimes leads to misunderstandings, where people seem to be speaking different languages when in fact they are working toward the same goals:

AI ethicist 1: “I think we ought to invest more in education to raise AI literacy. Helping young students reflect critically on technology is important.”

AI ethicist 2: “Yes, I agree education is important but it takes too long and is not guaranteed to work either. Shouldn’t we focus our efforts on regulation to address algorithmic biases? That would have more immediate impact.”

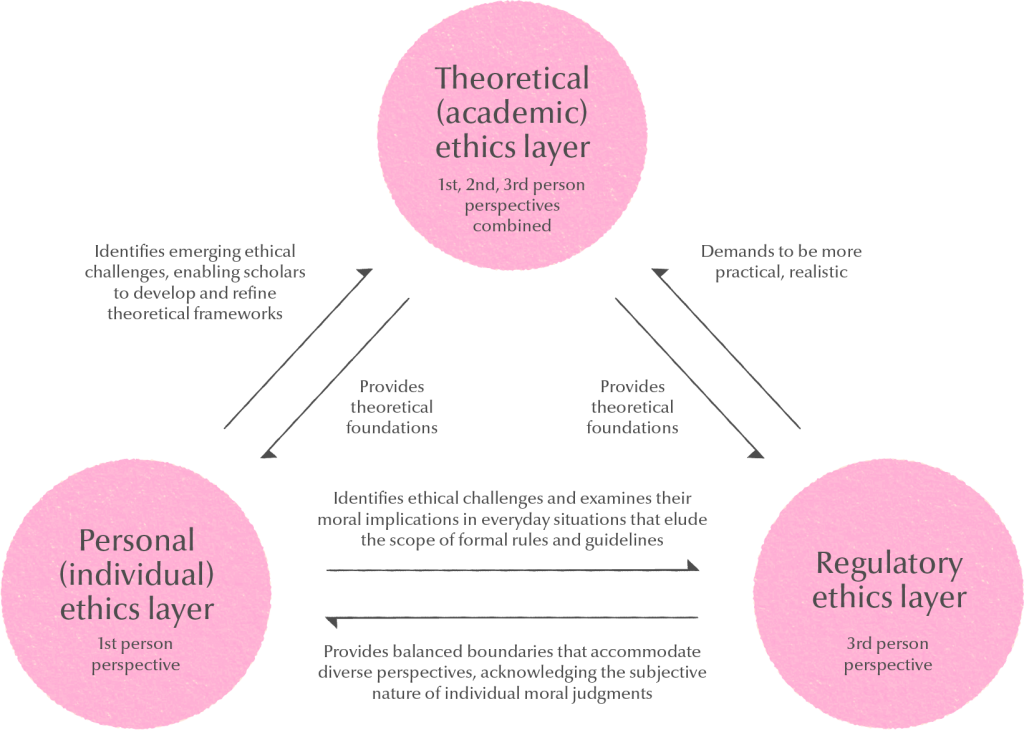

In this context, Professor Gwang-Soo Mok’s framework offers a timely and more comprehensive understanding of AI ethics. He proposes that AI ethics operates across three complementary layers: regulatory, individual, and theoretical. (The technical fixes and regulations we’ve discussed above would fall within the regulatory layer.)

Particularly significant is the individual layer, which has been largely absent from AI ethics discussions. This layer encompasses two groups: developers (including all practitioners involved in AI development) and users. While developer-focused initiatives like embedded ethics programs have received some attention, the user dimension remains largely unexplored. Yet this latter aspect is also crucial: ensuring users can engage with technology with a critical perspective, guided by internalized ethical awareness. Hagendorff’s critique of “trustworthy AI” illustrates this point well. He argues that encouraging blind trust in AI systems could be problematic — proactive skepticism from users can be healthier when dealing with powerful technology.

“Trust is itself a risky endeavor. The resulting benefits of a trust relation may not counterbalance the disadvantage of the breach of trust. Trusting too much is always imprudent. That is why mistrust can be very important, especially regarding powerful technological artefacts. Mistrust leads to a situation where individuals do not ignore risks, but perceive them as such and react appropriately. Trustworthy AI may thus be the wrong goal to aim at.”

But how do we cultivate such critical awareness? This is where things tend to sound a little abstract, especially in comparison to regulation and technical fixes where implementation is clear-cut. Currently, our tools seem limited to producing more public content, running literacy programs, and hosting public debates at best. There is a need to explore more creative approaches to engage individuals in shaping their relationship with AI technology. We could, for example, consider fostering greater collaboration between AI ethics communities and researchers with storytellers, filmmakers, and artists to create more engaging content and experiences that can help the public better understand and reflect on AI’s ethical implications. Such partnerships could help make complex ethical discussions more tangible and relatable for the general public – and there are likely many other approaches we haven’t explored yet.

Nevertheless, this is a good starting point. While such ‘bottom-up’ approaches are often criticized as idealistic or even elitist, it’s important to remember that part of their value lies in how they complement other layers of AI ethics, according to the three layers framework. Rather than viewing the individual layer as a less effective standalone initiative, we should recognize how it can strengthen the regulatory framework: individuals equipped with internalized ethical awareness can address gaps that guidelines alone cannot fill, thus reinforcing the guardrails set by the regulatory layer.

Cultivating meaning

At DAL we have been advocating resistance to reduction, where the danger lies in trying to simplify complex debates to make them computationally tractable, resulting in implementations that are straightforward but conceptually shallow. The current AI ethics practice seems like a prime example of this reductionist tendency, focusing heavily on technical fixes at the expense of deeper ethical engagement.

We should pursue ethics as a process, not technological solutionism – it’s important to recognize that ethics is an ongoing journey of deliberation rather than a fixed destination. Viewing the practice of AI ethics as an intricate relationship between different layers that need to be cultivated offers us a helpful framework for navigating these complex times. Particularly, we see significant potential in the individual layer and aim to explore and experiment with diverse approaches moving forward.

Joseph Park is the Content Lead at DAL (joseph@dalab.xyz)

Illustration: Soryung Seo

Edits: Janine Liberty