Introduction

DAOs (digital autonomous organizations) are lightweight structures for governance, and provide tooling for action and direction of funds without need for setting up a company in the traditional way. Minus the legal incorporation paperwork, the time it takes to set up a bank account, and the energy for payroll logistics, someone can start a DAO and start paying people for their work within a day.

💡 It’s important to note here that DAL does not endorse illegal short term activities — if there are any associations of real world assets involved, like owning inventory, legal wrappers need to be set up. On another note, Japan is working on allowing more legal forms of DAOs — you can follow the updates here.

However, not all things need to be DAOs — there are certain important nuances to keep in mind. This article will go through the general steps to set up a DAO, an overview of the tooling infrastructure, and the most important ingredients of a successful DAO.

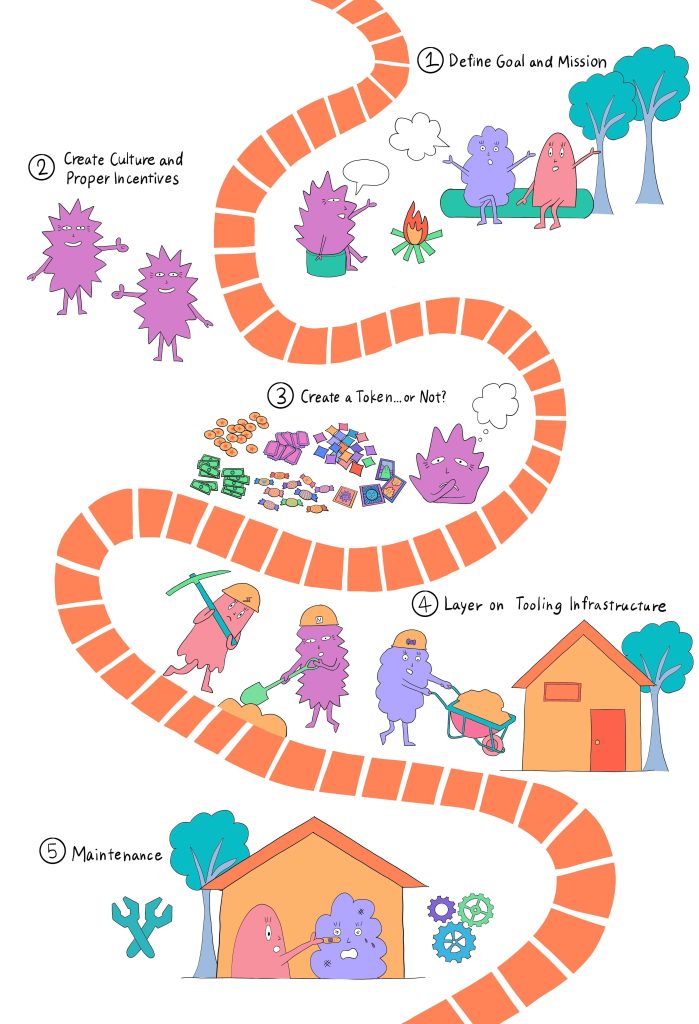

Step 1: Define Goal and Mission

The first couple of steps are similar to how anyone would set up a company or organization, and starts with defining a certain collective objective. As DAOs require coordination across diverse online agents (especially for those who may not know each other), and have contributors who work under anonymous accounts, having a coherent goal that members can work together on is key.

💡The decision-making process in a DAO is inherently decentralized, through both voting (proposals) and action (execution of proposals). As contributors may not have shared historical context, or reasons to trust each other, it is imperative that they at least have trust in the tooling and platform that the DAO infrastructure is hosted on.

We’ll get into this a bit more later in the article, but the kind of tooling and incentive structure that a DAO needs will depend on the goal / mission that it is trying to achieve. A DAO fund will have more emphasis on its financial security, while a community DAO will require more content, forum posts, and vehicles for interaction. Many DAOs may become hybrids, but it is important to have a streamlined and defined approach, at least initially. This mission will be the core foundation that everything else is built upon.

Before creating a DAO, one of the main questions to ask is if a DAO is really necessary to accomplish the goals of your project. While lightweight in some ways, there are also additional obstacles to figure out, like legality / owning assets in the real world, or what kind of incentives should be encouraged in the organization. Oftentimes these bridges may make the operations and regulatory side more complex, so make sure to research properly before determining if creating a DAO is the best approach.

Step 2: Create Culture and Proper Incentives

For the most part, the culture will dictate what the incentive design and system structure look like: will the DAO operate more like a true democracy or benevolent dictatorship?

💡 While there can be an initial definition, the culture will ultimately emerge from the group of participants involved, and in turn impact the governance structure and degree of decentralization or automation. In the most extreme case, the DAO operations can be fully mechanized via programmed smart contracts that interact with each other.

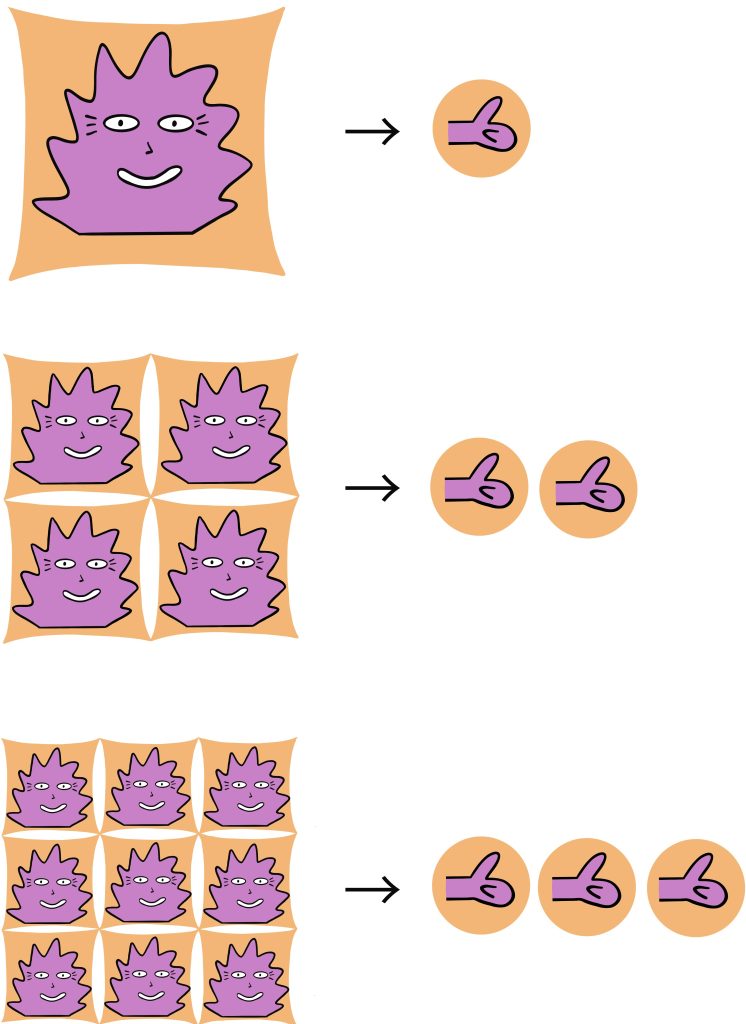

In the previous article, we mentioned that web3 unlocks an opportunity to program incentives. As an example of how programmable contracts can change incentives: a DAO can implement an algorithmic tool called “quadratic voting” to incentivize and promote a diverse stakeholder base over one that biases a few holders with large financial capital.

Traditionally, in the web2 world, the amount of governance power is largely determined by how much equity you have: i.e., owning one share provides you with one unit of voting power. However, quadratic voting decreases voting power in proportion to how many tokens you own. This allows for voices from a more diverse group of shareholders to have power.

DAOs can also implement processes like elections, where votes are delegated to the wallet / user of your choosing, and they can make decisions for their constituents (even though they keep their tokens). This kind of embedded meta-structure allows for voting from an informed population and also prevents “whales,” or people that own a large percentage of the tokenbase, from monopolizing decision making, or colluding to direct DAO funds in self-interested ways.

This is akin to a kind of micropolitics — but instead of choosing from a certain set of incumbents, you can delegate your votes to practically anyone, including yourself. Councils are growing in popularity, as it is sometimes difficult for the average user to keep track of context over time, since DAOs tend to evolve quite rapidly.

💡 Additionally, a DAO can also assign different weights of voting to “earned” tokens, or ones distributed to contributors, instead of purchased ones. For example, an “earned” token could have 3x the voting power of a “purchased” token: this allows for users that have contributed to have a larger say in what happens to the project, and prevents dilution from financial investors, even though the latter may still be important (and still therefore necessary to incentivize) to provide financing and capital to the project.

These are only a few examples, but the flexibility to the inherent reward system and governance system will greatly impact how change occurs, and how culture is maintained and iterated upon over time.

While a DAO founder can start with some general principles, keep in mind that the culture will always be evolving based on the members: a 100-person DAO feels very different than a 1,000-person one. Over time, as organizations scale, there naturally becomes less trust between people, and attract those who may join for profit, rather than innate alignment or interest in the mission.

Step 3: Create a Token… or Not?

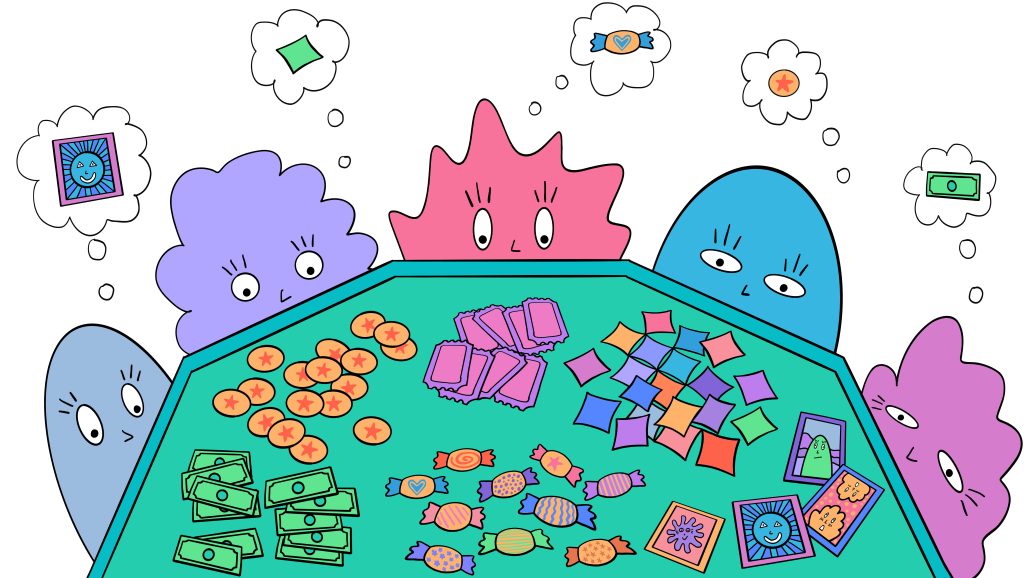

After fleshing out different reward systems, there needs to be some kind of mechanism for distribution of the rewards: welcome to the world of tokenomics. There are many resources that can guide a founder through the process of deploying the token to the blockchain (such as this one for ERC-20), but we won’t get into too much of the technicalities here.

What we will get into are the questions that will inform what kind of token will be most relevant for your project. First, it’ll be important to answer these questions:

- What kinds of things do you want to incentivize?

- This is related to how you created culture in the previous step.

- If you want to focus more on community and cultural elements, non-fungible tokens will be useful as they are perceived as personal artifacts, or items that people can associate with their identity

- For financial liquidity, fungible tokens are more suitable.

- For reputation, non-transferable tokens or ecosystem tokens are important to signify assets that cannot be sold on the open market, and stays with a specific wallet.

- Who are the main stakeholders for involvement?

- This will determine your go-to-market strategy, price points for token launch, as well as how you build community.

- If the stakeholders are more business-type customers, this may warrant a higher price premium, but also more customization, or use of white-glove service.

- If the user base is made up of individuals, focusing on general community cohesion, governance, and engagement may be key.

- How do you intend to sustain your project financially?

- If most of the revenue is expected to come with price appreciation of the token, a limited supply may make more sense.

- For more IRL perks / sales, having continuous distributions, or seasonal sales of tokens or memberships could be a good way to maintain momentum while making use of the existing treasury.

- What chain do you want to launch on?

- ETH is the most popular for basic utility applications on the blockchain, but there have been more chains popping up due to their cultural nuances.

- Solana prides itself on being more environmentally friendly and efficient from a computational standpoint; IBC is known for its interoperability and scalability.

- Additionally, there are also many layers that are building on top of ETH, like Arbitrum, Optimism, or Polygon — these make transaction costs more efficient and therefore cheaper (which is helpful for more frequent governance, as voting for proposals typically require transaction costs), but generally have less volume and market exposure than ETH.

- Check out more comparisons in this article here

- If there is a certain chain you’re curious about, there usually is a community / network of people who are actively working on the chain that can help get you acquainted with it. We would recommend getting to know developers and people who are building on the chain to see if there is resonance with your work as well.

- ETH is the most popular for basic utility applications on the blockchain, but there have been more chains popping up due to their cultural nuances.

There are many more nuances, but these are some basic questions to get you started. The answers to these questions will help you gain clarity on a general framework for the kind of tokens you may want to create.

💡 Remember that it is possible to also prototype a minimum viable product (MVP) without being officially on the blockchain, meaning you can start playing around with testnet tokens, or even ecosystem points that are not on the blockchain (AKIYA does this, for example). This allows for you to play around with incentive structures, collect data from participants, and see what sticks before getting too deep into the tokenomics theory.

Tokens allow for wallets to hold assets on the blockchain — this unlocks interoperability with other DAOs and web3 projects. For instance, this could allow for potential partnerships, whitelisting, or credibility with other DAOs (i.e., holding credentialing from Rabbithole, a web3 education platform, could automatically allow someone to qualify for a bounty assignment elsewhere). On the other hand, if your focus is more on growing your own community, ecosystem points are a great way to sandbox an initial environment faster, and in a more iterative way.

Usually by the end of this step, which generally requires the most rigorous analysis and research, findings and rationale are consolidated in a published white paper.

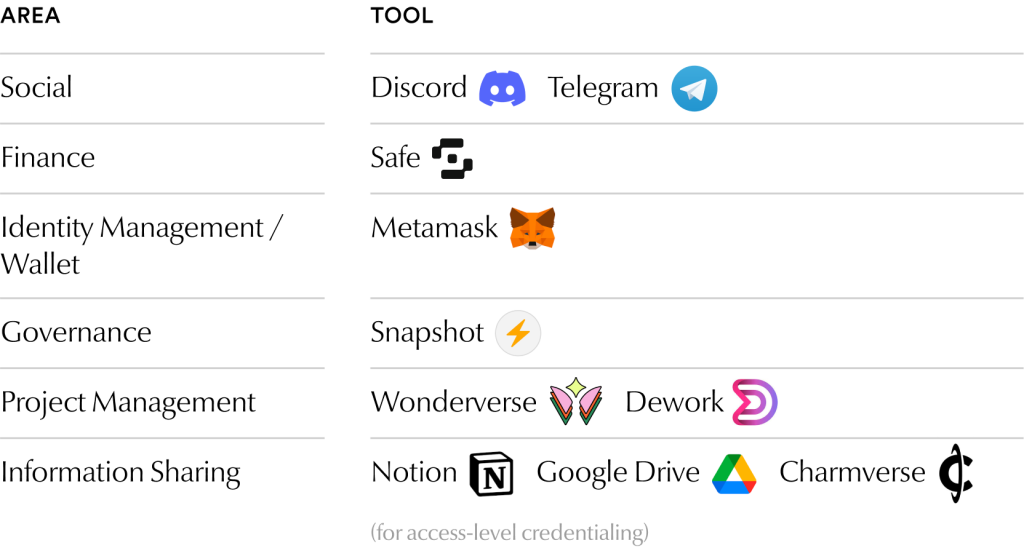

Step 4: Layer on Tooling Infrastructure

Creating a DAO usually just starts off as a community chat for coordination. However, tooling is layered on as needed: this helps transition a liminal organization into something more structured — and allows for multiple parties to coordinate dynamically to achieve the outcome of the project.

As mentioned before, DAOs are composed of members that may not have reasons to trust each other, so there must be mutual trust on the tooling infrastructure. For example, a newcomer may not have a personal relationship with the existing DAO administrators, but if there is history of contributors being paid for their tasks (or if smart contracts automatically are programmed to send crypto to wallets after the completion of tasks), then there is implied trust that they will be paid for their work. An equivalent in today’s world may look like this: an Uber customer may not need to know the driver personally in order to feel confident that they will arrive at their destination safely – having trust in the platform is enough.

💡 In this regard, the tools and underlying infrastructure of a DAO allows for this strata of connectedness — at a base layer, newcomers may have trust in the system, and not initially with each other until reputation is built through repeated interactions. This reputation is also interoperable between platforms, as wallet history is transparent to everyone on the blockchain, which makes it easier for contributors or leaders with a substantial reputation to prove credibility based on their previous work.

In the same way, bad apples that may have scammed in the past, can now be permanently flagged (that is, until they create a new wallet with no history). This kind of reward and identity management maintains an individual’s data and credibility from multiple sources, especially if they are contributing to different DAOs.

It’s important to note that any additional tooling shouldn’t get in the way of coordination, as that reduces the point of adding it in the first place. A common pitfall of DAOs is that members try to automate things too quickly — when this happens, it loses the human touch, community aspect, and may end up making the DAO inactive. Initially, it’s helpful to start with as little tooling as necessary, as the members find a centralized platform to coordinate, and as they get used to the cadence of the project.

Here’s a table that lists out some of the common tools that DAOs use in different areas:

For more information about legal DAOs in Japan, check out the meeting notes from the local DAO meeting in Japan LDP white paper. These initiatives in Japan are actively working on legalizing DAOs in this country.

Step 5: Maintain the DAO over Time

Finally, let’s talk about maintenance, an oftentimes overlooked part of starting a DAO. These structures require constant energy over time. They are living, growing, evolving entities that change when their constituents change.

💡 While DAOs can eventually become more autonomous, these organizations are still dynamic organisms and usually start as more centralized initially. This means that they will undergo many adaptation periods over the course of their lifecycle. Decentralization doesn’t happen all at once, but progressively over time.

Especially at first, there is a need for a structure, or things may turn into chaos, akin to Twitch playing Pokémon: an internet phenomenon where someone live-streamed a bot playing a Pokémon game on Twitch, where each message in the chatroom was mapped to a keystroke in-game. If there is structure, that means that someone, or a group of individuals, need to define it.

It is important to note here that so many things are good in theory, but don’t work in practice: as much as someone can philosophize or hypothesize about the perfect structure of a DAO, the structure largely depends on the constituents. Due to DAOs being so liminal by nature, contributors may vary in their activeness, especially if the compensation is not equivalent to a full-time salary.

💡 Certain needs evolve in response to this, like having a centralized information sharing platform. Generally, it is important to keep culture / foundational mechanisms coherent and present, so the culture has a grounding force, but also enables some fluidity as well.

DAOs are containers for these behavioral iterations to occur — we are still answering questions like: what kind of incentive structure allows for more long-term sustainable work to be done over time? If we are talking about long term sustainability, it becomes especially important not to get caught in the hype / degen cycle that some of the crypto world is associated with. While DAOs may change in many ways, social and public accountability is important to maintain credibility even through multiple rounds of evolution.

Summary and Recap

To summarize, DAOs are a more lightweight version of a traditional organization, with necessary trust in the tooling infrastructure and ability to experiment with different incentive design systems. While they initially may take less work to spin up, they frequently also require legal entities that map to their operations, so a question to ask before creating a DAO is if you really need one.

Defining a coherent mission and building culture is an incredibly important task for a DAO to operate successfully, as it will dictate what kinds of incentive design will be implemented. This will also inform other decisions like tokenomics, the amount of decentralization, and tools needed for the DAO to operate successfully.

On the tooling front, these tools should enhance coordination, and not get in the way of it; to allow for contributors to onboard cohesively, they should be slowly introduced, and with robust documentation. It is a common pitfall for tools to become distracting to the coherent mission of the DAO, as people may spend more time documenting or finding information, rather than contributing. Coordinating properly must be the highest priority for the DAO meta-structure.

In the same way, the structure of the DAO should reflect the vision and values of the group more fully, not take away from it. These experimental environments allow us to answer questions like:

- How do we create containers for this to occur and more rapidly?

- How do we allow structures to reflect the will of its constituents, instead of extracting from them “current state of human resources: work / labor as a commodity”

💡 So often individuals are exploited to fulfill or propel the will of the company; DAOs represent an interesting way that we can allow for more ownership, both psychologically and from a financial upside point of view — for contributors to be properly rewarded with the growth of an organization, and not just the financial shareholders.

Creating a DAO has a much lower bottleneck than creating a traditional company, and has allowed for more grassroots organizers to rally and reward aligned people on their missions. In this regard, we have the capacity to learn more about distributed coordination, and collectively explore and find frameworks that previously were siloed behind organizational walls. With the ethos of transparency, knowledge sharing, and teamwork, anyone can contribute to this open-source network of teams working together on aligned missions.

The ethos of DAOs is centered around participation, governance, and collective action. Because of this, every voice counts — ranging from those who are already very familiar with the web3 space, to those who are completely new.

We’ve provided a space for you to get involved in the discussions with our community below. Feel free to add your answers, quote tweet the article with “#DALDAODiscussion” for relevant comments, and share your viewpoints with each other.

The landscape is constantly shifting; this is an invitation for you to join the conversation and help collectively shape the future of DAOs together.

Discussion Questions

- If you were to create a DAO, what would its mission be, and what are some incentive structures you would be interested in experimenting with?

- What are some examples of organizations that have created a strong culture or brand?

Michelle Huang is an Experience Architect at DAL. She is creative technologist and founder of Akiya Collective. (michellehuang42@gmail.com)

Illustration: Asuka Zoe Hayashi

Edits: Janine Liberty & Joseph Park